I like to boast about regional differences, in the sense that Cascadia, home to the Silicon Forest, is pioneering a more useful STEAM curriculum than you'll find in most parts of the world, including in the UK, which sets the pace for many US east coasters, in the form of standardized testing.

But does this regional curriculum actually exist and what does it look like? Simply to remain true to its roots, it'll need to focus on "chips" meaning logic gates, boolean algebra, ALUs, CPUs, GPUs and all that. Plus 'learning to code' will be integral with learning mathematics.

The above MIT Scratch application, very simple, suggests how we bridge lexical and graphical. The coding environment itself is a mix of lexical and graphical elements, with the language defined in terms of "blocks" looking like jigsaw puzzle pieces.

By taking the XY and XYZ Cartesian apparatus of, building on what we learned earlier with figurate and polyhedral numbers ala The Book of Numbers (Conway & Guy) and Gnomon (Gazale), we bridge from mathematics to architecture and visualizations more generally.

Mere calculators won't get us there. We need real computers to learn our maths.

We need to embrace 3D printing and CAD skills, and what used to be called "mechanical drawing" (making blueprints).

Fig. 988.13C S Quanta Module

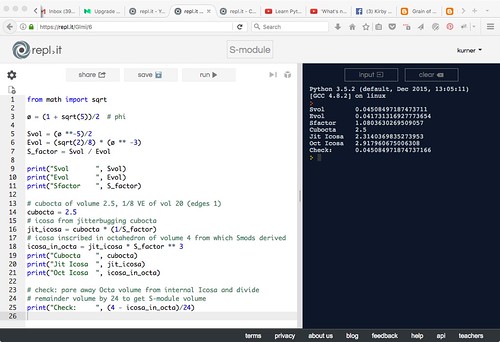

For example, tetrahedron EFGH above is called an S-module and 24 of them applied to the faces of the internal icosahedron, build this octahedron of 4 tetravolumes.

Starting with a smaller cuboctahedron of volume 2.5 and applying the S-factor twice, we get this icosahedron's volume.

Subtracting this icosahedron's volume from 4, and dividing the difference by 24, gives the S-module's tetravolume of (ø^-5)/2.

That's right, unlike the east coast curriculum, the Silicon Forest is friendly to the Bucky stuff.

MIT was somewhat friendly, at least when Dr. Loeb was alive, but Boston's public schools recently chose to go from the Mercator to the Peters Projection, without mentioning Fuller's.

Maybe New England no longer appreciates American Transcendentalism (Fuller being the grandnephew of Margaret Fuller, early editor of Dial), but we do.