This story of Howard Hughes appears to check out on every level. The things I'm still learning...

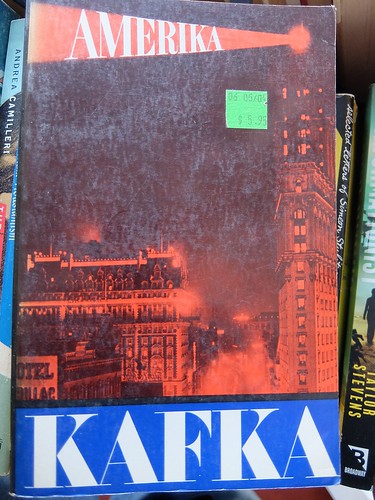

Just this First Day at Quaker meeting, when checking out the rack of books on sale for fund-raising, I stumbled upon Kafka's first novel Amerika, published posthumously, who knew? Not me.

It's not a like a fancy Princeton education back in the day made me a know-it-all. On the contrary, my time in Firestone Library reinforced my appreciation for the power of browsing freely (it's open stack, at least to students).

The advent of the web browser, after I'd left (Class of 1980) further amplified our global reach, ala the vision of MEMEX shared by Dr. Vannevar Bush, in a famous article, in Atlantic Monthly.

I've been describing "different species of capitalist" on Facebook, ranging from "bling capitalist" (more Las Vegas, more showy, ties to organized crime) to the reclusive relatively low profile type.

Howard Hughes played it both ways: high profile in his youth, then tapering off to ever-lower profile, keeping his cards especially close to his vest when the public was supposed to think him dead.

Warren Buffet (Oracle of Omaha) is more middle of the road. My taxonomy is not fully fleshed out yet.

US Presidents may come from the rough and tumble organized crime side of the business (e.g. the Kennedy brothers), wherein "bling" is big. Thanks to Prohibition, huge sectors of the economy had become criminalized. Amerika was a nation of scoff-laws and sinners.

No one knows the inner psyche of Americans better than the Mafia, the industry in charge of catering to forbidden desires. No wonder Nixon got in.

The Silicon Forest capitalist, in contrast to the "bling" school, has a more egalitarian dress code, with net worth inversely correlated to the presence of a neck-tie.

The management structure is also "flatter" or "thinner" in many ways (fewer levels or ranks), more Pacific Rim, more Japanese, with less towering of software and hardware engineers over one another.

Grounded in the sciences, engineering is more about shared humility before nature. The ability to intimidate is hardly the point, when dealing with cosmic forces and exceptionless principles (Van Allen Belts and so on).

The Quaker capitalists of the roaring 1790s were less tycoon-tyrants or "rubber Barons" (as in Fitzcarraldo) than experimentalists in management theory. The ideal of a workers' paradise loomed large in these early days of automation (freedom from dirty jobs).

This ideal proved threatening to satirists with an investment in the status quo. George Bernard Shaw took on Cadbury. Having well-treated workers made everyone else look bad. Demonizing any such ideology as necessarily "anti-capitalist" (i.e. "socialist" or "communist") would be a future innovation.

The exploiter class needed to keep the standards low and therefore frustrate any lofty Quaker visions. "Go to Pennsylvania if you want to try out those zany experiments" was the word from on high, from the would-be competition.

William Penn's forestland ("Sylvania") would be our Quaker utopia. Didn't happen. Indian Wars came instead.

Neither health care nor education was a part of the deal in Oliver Twist's merry England. The public laws more about the ones on top, staying on top, than anything more broadly constructive for the common people.

That status quo explains the American Revolution in large degree. Idealism doesn't like to be frustrated at every turn, needs creative outlets.

Even if no generation seems to "finally arrive" in the Promised Land, there may still be a sense of direction, a sense of continuing to escape tyranny.

Just this First Day at Quaker meeting, when checking out the rack of books on sale for fund-raising, I stumbled upon Kafka's first novel Amerika, published posthumously, who knew? Not me.

It's not a like a fancy Princeton education back in the day made me a know-it-all. On the contrary, my time in Firestone Library reinforced my appreciation for the power of browsing freely (it's open stack, at least to students).

The advent of the web browser, after I'd left (Class of 1980) further amplified our global reach, ala the vision of MEMEX shared by Dr. Vannevar Bush, in a famous article, in Atlantic Monthly.

I've been describing "different species of capitalist" on Facebook, ranging from "bling capitalist" (more Las Vegas, more showy, ties to organized crime) to the reclusive relatively low profile type.

Howard Hughes played it both ways: high profile in his youth, then tapering off to ever-lower profile, keeping his cards especially close to his vest when the public was supposed to think him dead.

Warren Buffet (Oracle of Omaha) is more middle of the road. My taxonomy is not fully fleshed out yet.

US Presidents may come from the rough and tumble organized crime side of the business (e.g. the Kennedy brothers), wherein "bling" is big. Thanks to Prohibition, huge sectors of the economy had become criminalized. Amerika was a nation of scoff-laws and sinners.

No one knows the inner psyche of Americans better than the Mafia, the industry in charge of catering to forbidden desires. No wonder Nixon got in.

The Silicon Forest capitalist, in contrast to the "bling" school, has a more egalitarian dress code, with net worth inversely correlated to the presence of a neck-tie.

The management structure is also "flatter" or "thinner" in many ways (fewer levels or ranks), more Pacific Rim, more Japanese, with less towering of software and hardware engineers over one another.

Grounded in the sciences, engineering is more about shared humility before nature. The ability to intimidate is hardly the point, when dealing with cosmic forces and exceptionless principles (Van Allen Belts and so on).

The Quaker capitalists of the roaring 1790s were less tycoon-tyrants or "rubber Barons" (as in Fitzcarraldo) than experimentalists in management theory. The ideal of a workers' paradise loomed large in these early days of automation (freedom from dirty jobs).

This ideal proved threatening to satirists with an investment in the status quo. George Bernard Shaw took on Cadbury. Having well-treated workers made everyone else look bad. Demonizing any such ideology as necessarily "anti-capitalist" (i.e. "socialist" or "communist") would be a future innovation.

The exploiter class needed to keep the standards low and therefore frustrate any lofty Quaker visions. "Go to Pennsylvania if you want to try out those zany experiments" was the word from on high, from the would-be competition.

William Penn's forestland ("Sylvania") would be our Quaker utopia. Didn't happen. Indian Wars came instead.

Neither health care nor education was a part of the deal in Oliver Twist's merry England. The public laws more about the ones on top, staying on top, than anything more broadly constructive for the common people.

That status quo explains the American Revolution in large degree. Idealism doesn't like to be frustrated at every turn, needs creative outlets.

Even if no generation seems to "finally arrive" in the Promised Land, there may still be a sense of direction, a sense of continuing to escape tyranny.