If you dig back into the early days of freeways and Detroit, and the future-world of the 1960s, Disneyland brand new, you'll find "traveling circus" caravans converging to schools, putting on corporately sponsored "futurama" shows. Am I right?; I remember looking into it.

Anyway, that's where the "bizmos" sometimes fit. I wasn't originally thinking food pods and food courts, which is where Portland and some other cities went with the idea. I'm not saying the food cart people read my blog or anything, just it makes sense for a van-sized vehicle to self contain some types of businesses. I thought that too.

When the vans or bizmos arrive at a school, they have some show or experience to create, lets call it a science fair and a kind of job fair. Students feel like they're being recruited, but usually with no way to make specific commitments, as these events are more informational than missionary. If you want to follow-up you'll be able to but the bizmos produce a standalone event. Something like that.

In one incarnation, these "GNU mobiles" would mostly be sharing the essentials of the POSIX world, already an esoteric place, where the typewriter starts talking back to your commands. An operating systems keeps a computer engaged with tasks, sometimes running in the background. I could as well imagine an Hour of Code van set to share Scratch or one of those block-based languages.

Today I signed up as a co-speaker on two Pycon 2017 proposals. That's the local North American one (so far, in radius), a "mother ship" in some ways, as the PSF showcases it as a model. Other Pycons use the trademarked name to certify a level or standard, not a new idea in business models, one with a proven track record. Finally, many Python (the computer language) related events may not use the "Pycon" trademark at all. PyOhio comes to mind.

The talks I signed up to co-speak about have to do with a scheme Charles Crossé wants to share publicly, having developed a working demo and used it with his own family. A use case would be a parent wanting kids at home to earn their play time on the web by winning at games deemed in advance to be suitably educational. Games may involve extensive readings, in other words I'm not always suggesting the stereotype "twitch game" associated with pinball and other arcade games.

Speaking of Python, what's going through my head these days was inspired by Trey Hunner's recent delving into the iterable : iterator distinction. The former category of object, if run through iter( ), will trigger an inner __iter__ that comes back with a new object containing __next__, thereby completing the iterator protocol. For example, an ordinary list object is an iterable with no __next__. Run it through iter( ) and a __next__ appears in the new butterfly-from-caterpillar iterator object.

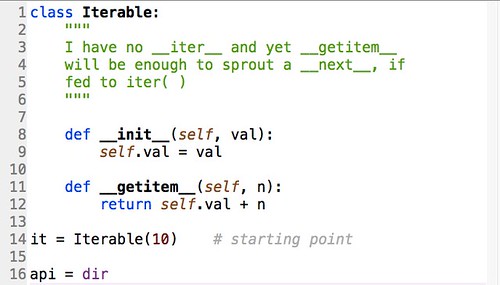

The plot deepens however, in that even __iter__ is not required, so long as a __getitem__ is present. The latter handles square-bracket indexing as in object[0], object[1], object[2]... The idea of "advancing an integer" from zero outward, is intrinsic to our notion of iteration. So if your class (type of object) at least implements __getitem__, then iter( ) will know enough to pull an iterator rabbit out of an iterable hat.

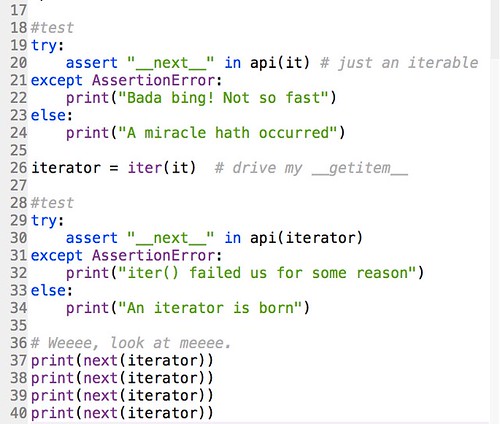

Here's the script. Iterable is a generic type with a way to set a starting value through __init__ (at birth), and then reflect the ever increasing value of n, as next( ) drives some internal __next__ to keep driving __getitem__. I'm not talking about code we anywhere write, as Python programmers. We simply count on next( ) to feed successive integers, starting from zero, to __getitem__, to "do the right thing" behind our __next__ calls.

Safe to say, your own __getitem__ may not be quite as simple as this one.

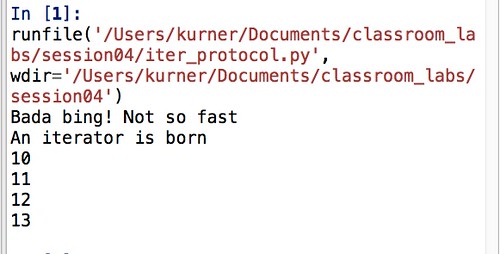

The output, showing "before" and "after" tests, with iter(it) run in the middle, returning a new object in which __next__ is indeed a part of the API (the "bag of tricks" associated with a class of object).

As Trey well explains, we don't necessarily use next( ) to drive the action. The for loop construct is precisely "that which uses an iterator" to iterate through some body (block or suite) of code.

When we get to the end of the rope and push passed the last in the series, should one ever be reached, a StopIteration is raised, which the for construct handles in stride as a simple signal to stop, with a possible run through an else clause if present.

The iterator later hatched into a full-fledged co-routine by way of the function generator concept. The keyword yield gives another way to provide a __next__, short of feeding anything through iter( ). A generator begins life as an iterator right out of the gate. We will pick up on their story in a future blog post.

Anyway, that's where the "bizmos" sometimes fit. I wasn't originally thinking food pods and food courts, which is where Portland and some other cities went with the idea. I'm not saying the food cart people read my blog or anything, just it makes sense for a van-sized vehicle to self contain some types of businesses. I thought that too.

When the vans or bizmos arrive at a school, they have some show or experience to create, lets call it a science fair and a kind of job fair. Students feel like they're being recruited, but usually with no way to make specific commitments, as these events are more informational than missionary. If you want to follow-up you'll be able to but the bizmos produce a standalone event. Something like that.

In one incarnation, these "GNU mobiles" would mostly be sharing the essentials of the POSIX world, already an esoteric place, where the typewriter starts talking back to your commands. An operating systems keeps a computer engaged with tasks, sometimes running in the background. I could as well imagine an Hour of Code van set to share Scratch or one of those block-based languages.

Today I signed up as a co-speaker on two Pycon 2017 proposals. That's the local North American one (so far, in radius), a "mother ship" in some ways, as the PSF showcases it as a model. Other Pycons use the trademarked name to certify a level or standard, not a new idea in business models, one with a proven track record. Finally, many Python (the computer language) related events may not use the "Pycon" trademark at all. PyOhio comes to mind.

The talks I signed up to co-speak about have to do with a scheme Charles Crossé wants to share publicly, having developed a working demo and used it with his own family. A use case would be a parent wanting kids at home to earn their play time on the web by winning at games deemed in advance to be suitably educational. Games may involve extensive readings, in other words I'm not always suggesting the stereotype "twitch game" associated with pinball and other arcade games.

Speaking of Python, what's going through my head these days was inspired by Trey Hunner's recent delving into the iterable : iterator distinction. The former category of object, if run through iter( ), will trigger an inner __iter__ that comes back with a new object containing __next__, thereby completing the iterator protocol. For example, an ordinary list object is an iterable with no __next__. Run it through iter( ) and a __next__ appears in the new butterfly-from-caterpillar iterator object.

The plot deepens however, in that even __iter__ is not required, so long as a __getitem__ is present. The latter handles square-bracket indexing as in object[0], object[1], object[2]... The idea of "advancing an integer" from zero outward, is intrinsic to our notion of iteration. So if your class (type of object) at least implements __getitem__, then iter( ) will know enough to pull an iterator rabbit out of an iterable hat.

Here's the script. Iterable is a generic type with a way to set a starting value through __init__ (at birth), and then reflect the ever increasing value of n, as next( ) drives some internal __next__ to keep driving __getitem__. I'm not talking about code we anywhere write, as Python programmers. We simply count on next( ) to feed successive integers, starting from zero, to __getitem__, to "do the right thing" behind our __next__ calls.

Safe to say, your own __getitem__ may not be quite as simple as this one.

The output, showing "before" and "after" tests, with iter(it) run in the middle, returning a new object in which __next__ is indeed a part of the API (the "bag of tricks" associated with a class of object).

As Trey well explains, we don't necessarily use next( ) to drive the action. The for loop construct is precisely "that which uses an iterator" to iterate through some body (block or suite) of code.

When we get to the end of the rope and push passed the last in the series, should one ever be reached, a StopIteration is raised, which the for construct handles in stride as a simple signal to stop, with a possible run through an else clause if present.

The iterator later hatched into a full-fledged co-routine by way of the function generator concept. The keyword yield gives another way to provide a __next__, short of feeding anything through iter( ). A generator begins life as an iterator right out of the gate. We will pick up on their story in a future blog post.